Golang

Panic vs recover

- To handle panics and recover from them in Go, the built-in panic() and recover() functions can be used. When an error occurs, panic() is called and the program execution stops. You can use the defer statement to call recover(), which stops the panic and resumes execution from the point of the nearest enclosing function call, after all deferred functions have been run.

Defer

- The defer statement in Golang is used to postpone the execution of a function until the surrounding function completes. It is often used when you want to make sure some cleanup tasks are performed before exiting a function, regardless of errors or other conditions.

Array vs slices

In Go, arrays and slices are both used to store collections of elements, but they have some key differences. Here’s a comparison between the two:

- Fixed Size vs. Dynamic Size:

Arrays: Have a fixed size determined at compile time. Once declared, the size cannot be changed. Slices: Are dynamically sized and can grow or shrink. Slices are references to sections of arrays.

- Access:

Arrays: Accessed using index notation. Indexes start from 0. For example: Slices: Also accessed using index notation. Slices can be sliced to get a subset of elements.

- Passing to Functions: Arrays: When passed to functions, the entire array is copied, which can be inefficient for large arrays. Slices: Passing slices to functions is more efficient because only a reference to the underlying array is copied, not the entire data. This allows for more efficient manipulation of data.

- Appending: Arrays: Cannot be appended to. Their size is fixed. Slices: Can be appended to using the append function. If the underlying array is not large enough to accommodate the new elements, a new larger array is allocated and the elements are copied over.

- Length and Capacity:

Slices: Have both a length and a capacity. The length is the number of elements in the slice, and the capacity is the maximum number of elements the slice can hold without allocating more memory.

- Usage:

Arrays: Used when the size of the collection is fixed and known at compile time. Slices: Used when the size of the collection may vary at runtime or when passing portions of arrays to functions.

Garbage collection

The garbage collector, or GC, is a system designed specifically to identify and free dynamically allocated memory.

Go uses a garbage collection algorithm based on tracing and the Mark and Sweep algorithm. During the marking phase, the garbage collector marks data actively used by the application as live heap(It first marks all live objects by traversing the object graph, starting from the roots). Then, during the sweeping phase, the GC traverses all the memory not marked as live and reuses it.

The garbage collector’s work is not free, as it consumes two important system resources: CPU time and physical memory.

The memory in the garbage collector consists of the following:

- Live heap memory (memory marked as “live” in the previous garbage collection cycle)

- New heap memory (heap memory not yet analyzed by the garbage collector)

- Memory is used to store some metadata, which is usually insignificant compared to the first two entities.

The CPU time consumption by the garbage collector is related to its working specifics. There are garbage collector implementations called “stop-the-world” that completely halt program execution during garbage collection. In the case of Go, the garbage collector is not fully “stop-the-world” and performs most of its work, such as heap marking, in parallel with the application execution.

Go routine

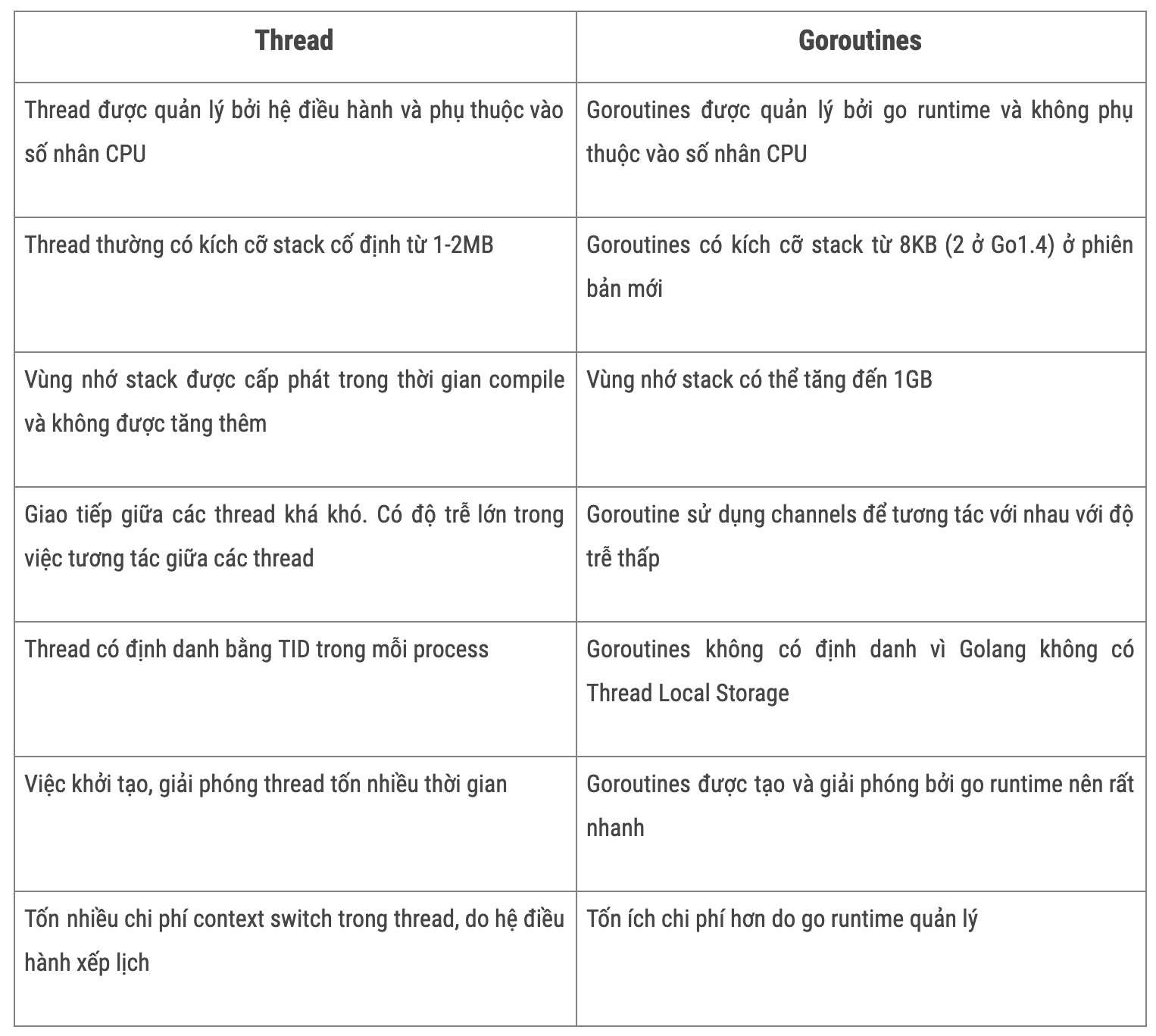

Go routine vs Thread

-

Go routines

-

Lightweight and concurrent units of execution in Go.

-

Advantages of goroutines: a. Lightweight and efficient compared to OS threads. b. Faster startup and lower memory consumption. c. Easy to create and manage with the “go” keyword. d. Ideal for concurrent programming and handling I/O-bound tasks.

-

-

Thread

- Higher Memory Footprint: OS threads typically have a larger memory footprint compared to goroutines due to their underlying system structures and management overhead.

- Context Switching Overhead: Context switching between OS threads incurs additional overhead as it requires system calls. This can impact the overall performance and scalability of an application.

- Suitable for CPU-Intensive Tasks: OS threads are better suited for CPU-bound tasks that require intensive computation. They can fully utilize the available CPU cores, allowing parallel execution of computationally intensive workloads.

- Manual Thread Management: With OS threads, developers have to manually manage thread creation, synchronization, and load balancing, which can be more complex and error-prone compared to goroutines.

Differences

Maximizing Parallelism with GOMAXPROCS:

-

GOMAXPROCS Configuration: GOMAXPROCS is a configuration parameter in Go that specifies the maximum number of OS threads that can execute Go code simultaneously.

-

Default Setting: By default, GOMAXPROCS is set to the number of logical CPUs available on the machine, allowing Go to automatically utilize the available cores for parallel execution.

-

Performance Optimization: Developers can adjust the value of GOMAXPROCS based on the specific workload and hardware characteristics to optimize the performance of their applications.

-

Balancing Act: Setting GOMAXPROCS too high may lead to increased contention and context switching overhead. Finding the right balance is crucial for achieving optimal parallelism.

Design pattern

- Fan-Out, Fan-In: Fan-Out: Launch a fixed number of goroutines to perform a task concurrently. Fan-In: Combine the results from multiple goroutines into a single channel.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

func worker(id int, jobs <-chan int, results chan<- int) {

for job := range jobs {

fmt.Printf("Worker %d processing job %d\n", id, job)

results <- job * 2

}

}

func main() {

const numWorkers = 3

jobs := make(chan int, 5)

results := make(chan int, 5)

var wg sync.WaitGroup

// Fan-Out: Launch workers

for i := 1; i <= numWorkers; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func(i int) {

defer wg.Done()

worker(i, jobs, results)

}(i)

}

// Fan-In: Combine results

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(results)

}()

// Send jobs to workers

for i := 1; i <= 5; i++ {

jobs <- i

}

close(jobs)

// Collect results

for result := range results {

fmt.Println("Result:", result)

}

}

- Worker Pool: Create a pool of workers (goroutines) to handle incoming tasks. Use a channel to dispatch tasks to available workers.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

func worker(id int, jobs <-chan int, wg *sync.WaitGroup) {

defer wg.Done()

for job := range jobs {

fmt.Printf("Worker %d processing job %d\n", id, job)

}

}

func main() {

const numWorkers = 3

jobs := make(chan int, 5)

var wg sync.WaitGroup

// Create worker pool

for i := 1; i <= numWorkers; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go worker(i, jobs, &wg)

}

// Send jobs to workers

for i := 1; i <= 5; i++ {

jobs <- i

}

close(jobs)

// Wait for all workers to finish

wg.Wait()

}

- Pipeline: Compose a series of processing stages, each implemented by a goroutine. Use channels to connect stages and pass data between them.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func generator(nums ...int) <-chan int {

out := make(chan int)

go func() {

defer close(out)

for _, n := range nums {

out <- n

}

}()

return out

}

func square(in <-chan int) <-chan int {

out := make(chan int)

go func() {

defer close(out)

for n := range in {

out <- n * n

}

}()

return out

}

func printer(in <-chan int) {

for n := range in {

fmt.Println(n)

}

}

func main() {

nums := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

gen := generator(nums...)

sqr := square(gen)

// Consuming the results

printer(sqr)

}

Go scheduler

The Go scheduler is responsible for managing goroutines, the lightweight threads of execution in Go. It follows an M:N threading model, multiplexing a large number of goroutines onto a smaller number of operating system threads. The scheduler uses a work-stealing algorithm to balance workload among threads and supports preemption to ensure fair scheduling. Developers can control the maximum number of OS threads using the GOMAXPROCS environment variable.